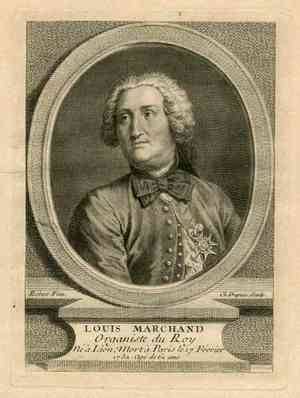

Louis Marchand

Source:

Gallica

Born in Lyon, France, on 2 February 1669, Louis Marchand arrived to Earth of a musical family, his grandfather a music teacher, his father an organist who also refurbished them. There is no relation between Louis and Jean-Noel Marchand (1666-1710), the latter known for his settings for Jean Racine's 'Cantiques spirituels' of 1694 [Gordon-Seifert / Musique Classique]. In the portrait above Marchand wears a powdered wig (powdered periwig, powdered peruke) which is one way you'd know that he occupied a high social tier. The wig came into fashion in France about 1655 when Louis XIV, Sun King, began the fad to hide hair loss perhaps as early as age seventeen. This is the cause for which his father, Louis XIII, wore a wig, and very likely the reason behind the famous red wig of Elizabeth I (1533-1603) in England before him. Hair loss was also a symptom of syphilis of which Louis very likely became victim at some time unknown. Louis probably fostered the wearing of wigs as a sign of status, aristocratic and otherwise, to avoid getting tagged the lonely only. Wigs were uncomfortably hot to wear, and a pain in the neck in general, yet status was sufficient cause to assume the fashion whether one was bald or not. Louis XIV epitomized the apex of monarchical power in France, a king baroque if ever one was amidst all the luxury and opulence of the Palace of Versailles [Château de Versailles / Wikipedia]. The great manes worn by Louis and his courtiers were fitting crowns to royal pomp. Louis employed 48 wig makers among the thousands who attended to his welfare. Yet he was modest in comparison to some the elaborate contraptions that women came to model. While common people or soldiers had little use for wigs, British King George II of England adopted them about five years after Louis XIV, and the fashion prevailed throughout the eighteenth century until it began to fade from style by the nineteenth. Wherever may that the wig or powdered wig dropped out of style among the upper classes it was largely due to association with the spoiled sweet monarchs of the 18th century who existed in other realms than the masses which were considered so much of the real estate over which they ruled. The dances for which Marchand wrote music occasioned sumptuous affairs which expense required small consideration with whole populations to pay for them.

King Louis XIV 1701

Painting of Louis in great waves of wig by Hyacinthe Rigaud

Marchand's patron 1708-1713

Source: Wikipedia

Baroque Hall of Mirrors of Louis XIV

One of numerous rooms representing decadence at the Palace de Versaille

Source: Jalon Interior

The more disciplined locks of the powdered wig were made court attire by Louis XIV's successor, his great-grandson, Louis XV, who was poster child of late baroque, that is, rococo, and whom Marchand served upon the death of Louis XIV. The wig powdered with chalk, flour or starch was thought to prevent lice but came in colors other than white and were often perfumed. The more tightly coiffed headdress of Louis XV effectively became a cap which any person who was somebody had no choice but don alike wearing a suit with tie today. The formalization of respectable stature via the wig famously continues to these times with British barristers atop their robes, but the practice largely ceased with successor to Louis XV, his son, Louis XVI, for this Louis arrived to no head on which to place a wig when he lost it at a guillotine on 21 January 1793, followed by his wife, Marie Antoinette, nine months later during the French Revolution leading to Napoleon's empire. Adopted in America as well, several presidents had worn wigs prior to taking office. George Washington (inaugurated 1789) had no need for the wig, though powdered and curled his own hair when not pulled back to the nape as was common. The wig fell out of favor in Great Britain due largely to the Hair Powder Act of 1795 requiring most but select groups to purchase certificates to powder their glorious bird nests, this a tax to help fund efforts in the face of Napoleon.

King Louis XV 1748

Painting of Louis in formal powdered wig by Maurice Quentin de La Tour

Source: Patrons

Rococo desk w clock of Louis XV

One of numerous rooms in style decadent at the Palace de Versaille

Source: Wikipedia

Marchand's family moved from Lyon to Nevers in 1684. Accounts differing, Marchand may or may not have become organist at Nevers Cathedral at age fourteen, but he was living in Paris by the time he was twenty, there to obtain employment at the Church of Eglise Saint-Jacques (Church of Saint-Jacques du Haut-Pas), documented in a marriage contract of 1689 to one Marie Angelique Denis, daughter of an organ builder [Wikipedia; some sources don't have him at Saint-Jacques until 1691].

Marchand's compositions are widely scattered in various manuscript compilations, mostly for organ, though he wrote obscure pieces for voice including a lost opera, 'Pyrame et Thisbé'. A cantata called 'Alcione' survives in manuscript. Of Marchand's works in name publication there are five, two printed posthumously, which can be enumerated here. These are two volumes for harpsichord, one for organ posthumous which is the first of four more not published, one book for violin with basso continuo, and a didactic treatise on counterpoint for liturgical voice, not determined when written but published posthumously.

Marchand published Book 1 of his 'Pièces de Clavecin' dedicated to Louis XIV in 1699 [dance order]. That saw its second edition in 1702 by Christophe Ballard along with Book 2 of 'Pièces de Clavecin' the same year, also dedicated to the king [dance order]. The first contained nine dances in D minor beginning with a prelude and finishing with a menuet; the second contained eight in G minor, again coursing through various forms, commencing with a prelude and wrapping with a menuet. Marchand's standard suite sequence isn't followed by harpsichordist, Ketil Haugsand, with either Book below, placing gavottes where Marchand puts gigues, nor wrapping with menuets. Why Haugsand alters Marchand's dance order I know not, but it's peculiar to Marchand's standard order followed by Ewa Mrowca, Davitt Moroney and Christophe Rousset. Yago Mahúgo also adheres to Marchand's standard sequence, though switches the order of the gavotte and menuet in Book 1.

Suite in D minor of Livre Premier of 'Pièces de Clavecin' by Louis Marchand

Pub 1699 2nd Edition 1702 Harpsichord: Ketil Haugsand

Suite in G minor of Livre Second of 'Pièces de Clavecin' by Louis Marchand

Pub 1702 Harpsichord: Ketil Haugsand

In the meantime it was circa 1700 that Marchand had composed Book 1 of 5 for organ as edited by Alexandre Guilmant. This was 'Pièces Choisies pour l'Orgue' consisting of 12 pieces addressing ecclesiastical tones beginning with 'Plein Jeu' now thought to have seen print as early as 1732 soon following Marchand's death. His other four unpublished books of organ pieces are thought to have been completed by 1708 when Louis XIV assigned him to organ at the Royal Chapel at Versailles. The second came in two parts, the first of 12 pieces, the second addressing the 'Te Deum' with 15 pieces. Volume three is a dialogue authored in 1696 followed by a fourth book of 6 pieces and a fifth of seven.

'Pièces Choisies Pour L'Orgue' by Louis Marchand

Book 1 of 'Pièces d'Orgue' Comp c 1700 Pub 1732 or 1740

Organ: Michel Chapuis

'Te Deum' by Louis Marchand

Book 2 Part 2 of 'Pièces d'Orgue'

Organ: Stuart Taylor Voice: Aidan F. Hill

'Grand Dialogue du 5e Ton' by Louis Marchand

Book 3 of 'Pièces d'Orgue' Comp 1696

Organ: Mark Rich

One date which holds true in all sources is 1701, the year Marie Angelique divorced Marchand for beating her. She then spent the next several years putting claim to half his earnings, acquiring the assistance of Louis XIV who agreed that such was fair. Marchand's virtuosic abilities seemed to win him grace from various unpleasant behaviors, he getting assigned to every fault in the book from belligerence to paranoia to emotional instability to simply a "bad" fellow altogether. Howsoever damned by his critics, Marchand worked at numerous churches in Paris throughout his career including the Church of St. Honoree from 1703 to 1707. Which arrived first is undetermined but in 1707 Marchand's 'Suite de Pieces Melee de Sonates pour le Violon et la Basse' appeared in print as well as pieces for harpsichord called 'La Vénitienne' and 'La Bandine' added to a collection by Ballard titled 'Pièces choisies pour le clavecin de différents auteurs'.

As mentioned, in 1708 Marchand was appointed to organ at Louis' Royal Chapel at Versailles. It was during Marchand's time with Louis that the latter completed the fifth rebuilding of the Royal Chapel in 1710 [Chateau de Versailles / Chateau de Versailles].

The anecdote goes that during the performance of a mass at the Royal Chapel at an unknown time Marchand stopped halfway through, explaining to Louis that since Marie Angelique received half his salary she might finish the mass as well. This manner of expressing it may have gotten him banned from Louis' court [Jander], for he is found on a concert tour of Germany between 1713 and 1717, during which time Louis XIV died in 1715, succeeded by his great-grandson, Louis XV. Marchand's return to France is said to have been hastened by a scheduled keyboard contest with J.S. Bach in Dresden in September of 1717. The story circulates that he left Dresden the morning of the scheduled duel due to fear that Bach would outperform him. That account originating in Germany varies from others which relate different reasons for missing his appointment with Bach [Classic FM / Georg Predota]. Whatever the causes that this baroque 'High Noon' got cancelled, Marchand returned to his position as organist at the Cordeliers Convent in Paris where he remained, also teaching for an income, until his death on 17 February 1732. Évrard Titon du Tillet's 'Description du Parnasse Francois' was published later that year in which he included his contemporaneous biography of Marchand. As observed, his first volume for organ, 'Pièces Choisies pour l'Orgue', may have seen print that year as well. Come his theoretical 'Traité de Contrepoint Simple ou Chant sur le Livre' in 1739 in which he addressed vocal counterpoint in sacred music.

Sources & References for Louis Marchand:

VF History (notes)

Jean-Marc Warszawski (Musicologie)

Audio of Marchand: Classical Archives

Compositions (see also Publications):

All Music Classic Cat Wikipedia English Wikipedia Francais

Publications:

Pièces Choisies Pour L'Orgue (comp c 1700 / pub 1732 or 1740):

(Book 1 of 5) Digital copy Digital copy

Pièces de Clavecin / Book 1 / pub 1699/1702:

Pièces de Clavecin / Book 2 / pub 1702:

Suite de Pieces Melee de Sonates pour le Violon et la Basse (pub 1707):

Traité de Contrepoint Simple ou Chant sur le Livre (pub 1739):

Digital copy Digital copy Digital copy

In English & Spanish as translated by Tim Braithwaite (downloads):

Cacophony! Early Music Sources

La Vénitienne (pub 1707)

Recordings of Marchand: Catalogs:

Discogs HOASM Music Brainz Presto RYM

Recordings of Marchand: Select:

The Complete Organ Works (Books 1-5) by Frank Taylor 2020:

Livre de pièces de clavecin, 1754 by Mario Martinoli 2005:

musica Dei donum MusicWeb International

Oeuvres pour orgue by Frédéric Desenclos 2011:

Scores / Sheet Music (see also Publications):

Pièces Choisies Pour L'Orgue (Book 1 of 5 collectively known as Pièces d'Orgue / comp c 1700 / pub 1732 or 1740)

Pièces de Clavecin / Book 1 / pub 1699/1702

Pièces de Clavecin / Book 2 / pub 1702

Pièces d'Orgue (anthology of 5 books as organized by Alexandre Guilmant):

Book 1: Pièces Choisies Pour L'Orgue (comp c 1700 / pub 1732 or 1740)

Book 2 Part 1: Deuxième Livre

Book 2 Part 2: Te Deum

Book 3: Grand Dialogue du 5e Ton (comp c 1696)

Books 4 & 5: (4e) & 5e Livre

Scores / Sheet Music (various):

IMSLP Musicalics (vendor)

The (Powdered) Wig:

Louise Boisen Schmidt Janel Torkington

Works (see Compositions / Publications)

Further Reading:

King Louis XIV (typical daily schedule)

Bibliography:

Berton-Blivet / Demeilliez / Davy-Rigaux (Anthologie d’écrits de compositeurs...Parus en France / 2014)

Mark Kroll (Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music / Taylor & Francis 2004)

Jean-Paul Montagnier (Le Chant sur le Livre au XVIIIe siècle / Revue de Musicologie 1995)

Andre Pirro (Quarterly Magazine of the International Musical Society Year 6 Part 1 / Breitkopf & Härtel 1905)

Geoffrey B. Sharp (A Forgotten Virtuoso / The Musical Times 1969)

Authority Search: BnF Data VIAF World Cat

Classical Main Menu Modern Recording

hmrproject (at) aol (dot) com